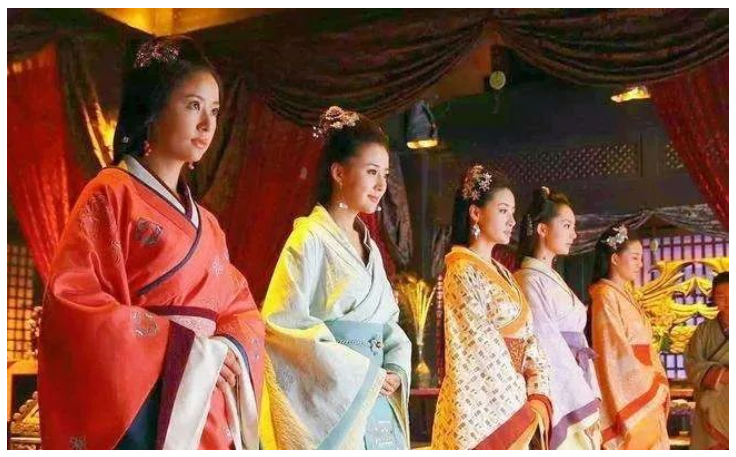

Have you ever watched a historical drama and wondered, “How much did those imperial concubines actually make?” It’s a question that tickles the curiosity of anyone who’s ever been fascinated by the opulent yet cutthroat world of ancient Chinese palaces. Well, buckle up, because we’re about to dive into the financial lives of these royal women, from their salaries to their spending habits. Spoiler alert: it’s not all silk and pearls!

The Han Dynasty: When Royalty Meets Payroll

Let’s start with the Han Dynasty, where the concept of a “paycheck” for concubines first emerged. The Western Han Dynasty was particularly generous. The Empress, being the top dog (or rather, the top dragon), didn’t need a salary—she had 40 counties’ worth of tax revenue at her disposal, known as her “bathing funds.” Yes, you read that right. Bathing funds. While it might sound like she was running the world’s most luxurious spa, this was essentially her personal allowance to spend as she pleased.

Below the Empress, there were 14 ranks of concubines, each with a salary comparable to that of a government official. The highest-ranking concubine, the Zhaoyi, earned as much as the Prime Minister—a whopping 10,000 shi of grain annually (one shi equals about 27 kilograms). Even the lowest-ranking concubines, like the Wuye, still took home a respectable 100 shi. Not too shabby for a gig that mostly involved looking pretty and occasionally plotting against your rivals.

But then came the Eastern Han Dynasty, and things took a turn for the worse. The imperial coffers tightened, and so did the concubines’ salaries. The Guiren, the only rank below the Empress, received a measly “several dozen hu of grain” per month. To put that in perspective, even the lowest-ranking officials in the Western Han Dynasty earned more. It’s like going from a CEO’s salary to an intern’s stipend overnight. No wonder the concubines were grumbling!

The Tang Dynasty: Royalty with Benefits

Fast forward to the Tang Dynasty, and the imperial payroll system became even more elaborate. Concubines were ranked similarly to government officials, with the Empress at the top, followed by the Guifei (Noble Consort), Shufei (Virtuous Consort), and so on, down to the lowly Cainü (Lady of Talent) at the eighth rank. Their salaries weren’t just in cash—they also received grain, land, and even servants. It was the ancient equivalent of a comprehensive benefits package.

But here’s the kicker: the Tang Dynasty was also known for its bureaucratic complexity. Calculating a concubine’s total compensation was like trying to solve a Rubik’s Cube blindfolded. There were base salaries, bonuses, and even “performance-based” rewards (though we’re not entirely sure what “performance” meant in this context). Still, it’s safe to say that life as a Tang Dynasty concubine was pretty cushy—if you could survive the palace intrigue, that is.

The Qing Dynasty: The Golden Age of Royal Allowances

By the time we get to the Qing Dynasty, the imperial payroll system had reached its peak. The Qing emperors were meticulous record-keepers, so we have a pretty clear picture of how much the concubines earned. The Empress, of course, was at the top of the pyramid, with an annual salary of 20 taels of gold and 2,000 taels of silver. She also received a generous supply of silk, fur, and other luxuries. But even the lowest-ranking concubines, like the Changzai and Daying, weren’t left out—they still got their share of pork, rice, and other daily necessities.

But here’s where it gets interesting: the Qing Dynasty also had a “bonus” system. On special occasions like birthdays or the birth of a royal child, concubines could expect a little extra something in their pockets. The Empress, for example, could receive up to 90 taels of gold and 900 taels of silver on her birthday. Meanwhile, the lower-ranking concubines had to make do with a few bolts of silk and some furniture. It’s like the difference between getting a Ferrari for your birthday and getting a gift card to IKEA.

Where Did the Money Go?

Now, you might be wondering: if these women were already living in the lap of luxury, what did they need money for? Well, it turns out that life in the palace wasn’t all lounging around and sipping tea. Concubines had to maintain their social networks, which meant giving gifts to everyone from the Empress down to the lowliest eunuch. And let’s not forget their families—many concubines came from humble backgrounds and sent money home to support their parents and siblings.

So, where did all this money come from? In the early dynasties, the imperial treasury was divided into two parts: the Da Sinong, which handled national taxes, and the Shao Fu, which managed the emperor’s personal finances. By the Qing Dynasty, the Neiwufu (Imperial Household Department) was in charge of the royal budget, and they got creative with their revenue streams—everything from taxing salt to fining corrupt officials. It was like a medieval version of a hedge fund, and the concubines were the beneficiaries.

The Bottom Line

So, did the imperial concubines have enough money to live comfortably? Absolutely. But as with any high-stakes job, the perks came with a price. Whether it was navigating the treacherous waters of palace politics or managing their finances, these women had to be shrewd, resourceful, and, above all, resilient. And while their lives might seem glamorous from the outside, the reality was often far more complicated.

So the next time you’re binge-watching a historical drama, spare a thought for the concubines. Behind all the silk and jewels, they were just trying to make ends meet—royal style.

No comments yet.