When the Tang dynasty poet 杜甫 (Du Fu) wrote “烽火连三月,家书抵万金” — “For three months war flames burned, a letter from home was worth ten thousand gold” — he captured something timeless: the priceless comfort of a message from a loved one. But in an age with no email, no WeChat, and not even a reliable postal service for commoners, how did people actually send letters?

Let’s step back into imperial China and unravel the surprising, often quirky, and deeply human ways people managed to stay in touch over vast distances and under the most difficult conditions.

Who Could Use the Postal System? Not You, Commoner!

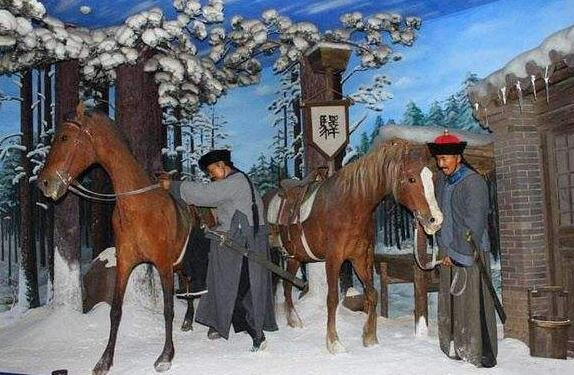

Today, when we think of ancient communication, the imperial postal relay system (驿站 yìzhàn) often comes to mind. And for good reason — it was a marvel of administrative logistics. Messages could travel hundreds of miles per day thanks to official couriers and relay stations stretching across the empire. The fastest designation? “五百里加急” — 500 li in a day, the equivalent of 250 kilometers!

But here’s the catch: this whole system wasn’t for you. It wasn’t for ordinary people at all. It was strictly for official use — emperors, governors, military commanders. In short, the elite.

If you were a regular citizen — a farmer, a merchant, a scholar — the imperial post wouldn’t so much as glance in your direction. In today’s terms, it would be like having a high-speed national courier service that only delivers government documents and refuses to touch personal mail.

So how did ordinary people send their heartfelt messages across provinces?

When Friendship Was the First Postal Service

The most common solution? Friends and acquaintances.

In a world without digital maps or guaranteed transportation, letter-sending relied heavily on the “who-you-know” network. If someone you knew was traveling in the direction you needed — bingo, you had a human mailbox.

A prime example: scholars taking exams. If a local xiùcái (licentiate) was traveling to the provincial capital for the xiāngshì (provincial exam), friends and neighbors might ask him to carry letters. If a jǔrén (successful provincial candidate) was heading to Beijing for the national huìshì exam, he became a walking post office for half the country.

Officials traveling for appointments or reassignment also got roped in. But this wasn’t always welcome.

Take the story of Yin Hongqiao, a fourth-century official from the Eastern Jin dynasty. After a trip to Nanjing, he was returning to his post in Yuzhang (modern-day Nanchang). Friends in the capital entrusted him with over a hundred letters to carry back. Overwhelmed, he reportedly tossed the entire bundle into the river and muttered, “Let the sunken sink, let the floating float — I am Yin Hongqiao, not a courier!”

Anyone who has traveled abroad only to be handed a shopping list for the duty-free shop can sympathize.

The Merchant Connection: When Business Carried Emotion

If depending on friends was unreliable, the next best option was to turn to the professionals of movement: merchants.

In imperial China, commerce flourished, especially during the Song and Ming dynasties. Merchant caravans routinely crossed provinces, braving long distances and rough roads. Since their business demanded regular travel, merchants made for ideal letter carriers — and they expected compensation.

Fees varied depending on distance and urgency. A short-distance delivery might cost a few dozen wén (copper coins), while longer or more urgent letters could cost over a hundred — roughly equivalent to a modern-day 100 RMB or more. Still, many found it worth the price for a letter that might carry vital family news or business updates.

Sometimes, the messenger was rewarded with more than just money. If the recipient was especially hospitable, the letter-carrier might be invited to stay for a meal — a small feast to celebrate a message well delivered.

Meet the Xìn Kè: China’s Original Freelance Couriers

Long before gig economy platforms or food delivery apps, ancient China had its own version of full-time messengers: the 信客 (xìn kè).

These were not merchants or casual travelers, but individuals who made a living carrying letters and small items for others. They operated in the gray area between necessity and trust — chosen for their reliability and willingness to endure the hardships of travel. They might go on foot, on horseback, or even by boat, navigating the dangers of terrain, bandits, and unpredictable weather.

The xìn kè often built a reputation over years, even generations. Some families became known for producing trustworthy couriers, and word-of-mouth spread their fame across regions.

Writer Yu Qiuyu captured this fading tradition beautifully in his essay “The Letter Carrier” (信客), reflecting on the dignity and hardship of those who carried the emotions of others across mountains and rivers.

Secrets in a Bamboo Tube

Protecting the letter itself was another matter. Ancient Chinese often placed their letters in narrow, sealed containers — usually bamboo tubes. These “postal tubes” (邮筒) safeguarded the message from rain, smudges, and prying eyes. The term “邮筒” first appeared during the Tang dynasty and is still used today in modern Chinese for mailboxes.

Aside from physical protection, the tube also symbolized respect. After all, a letter wasn’t just information — it was a vessel of emotion, reputation, and trust. Sending a letter in a damaged or poorly sealed form would be seen as careless, even disrespectful.

Carrier Pigeons: The Unreliable Wingmen

Of course, no discussion of ancient communication would be complete without mentioning pigeons.

Yes, carrier pigeons were used in China — but they were far less reliable than legend suggests. For starters, pigeons can only fly back to their home coop, not to any arbitrary location. So to send a message by pigeon, the sender had to carry the bird with them, then release it at the destination to return home.

And the risks were considerable. With no GPS and no guaranteed food supply, pigeons often got lost. Worse yet, they might get… eaten.

Certain regions were notorious for grilled pigeon. One town near modern-day Changchun, Yitong County, became so famous for its barbecued birds that it became something of a Bermuda Triangle for carrier pigeons — “in service” one moment, “on the skewer” the next.

To hedge their bets, senders often used multiple pigeons carrying identical messages. Even if a few failed to return, one might still complete the journey — a strategy of probability rather than precision.

Love, Distance, and the Weight of Paper

In the ancient world, the emotional weight of a letter far exceeded its physical one.

A message from home, from a lover, from a child far away — these were rare, precious, and often read and reread until the paper wore thin. The anticipation could last weeks or months. For lovers separated by long distances, a single letter could span seasons.

This emotional intensity is hard to recreate in the digital age. Today, a message can be sent in seconds. But back then, to write a letter was to crystallize feelings into something lasting. To send one was an act of hope. To receive one was an event.

In that sense, the old phrase 纸短情长 — “the paper is short, but the emotion is long” — rings deeply true. When you waited six months for a reply, you didn’t waste words. You poured your heart into them.

Final Thoughts

In our hyper-connected world, it’s easy to forget the ingenuity and intimacy of pre-modern communication. While today’s messages arrive in nanoseconds, ancient Chinese people relied on trust, timing, and tenacity to share words that mattered.

From traveling scholars to moonlighting merchants, from professional xìn kè to pigeon-messengers with a death wish, the human desire to connect has always found a way.

So next time you receive a text and forget to reply — remember Yin Hongqiao, who threw 100 letters into the river rather than deal with them. Or better yet, remember the thousands of unnamed letter-carriers whose footsteps crisscrossed China, carrying not just ink on paper, but love, longing, and life itself.

No comments yet.