China’s reverence for education stretches back millennia, forming the backbone of its enduring civilization. But behind this cultural ideal lay a grueling reality for students across dynasties. How did ancient Chinese scholars cope with academic pressures that would make modern students shudder?

The Surprisingly Relaxed Beginnings of Han Dynasty Learning

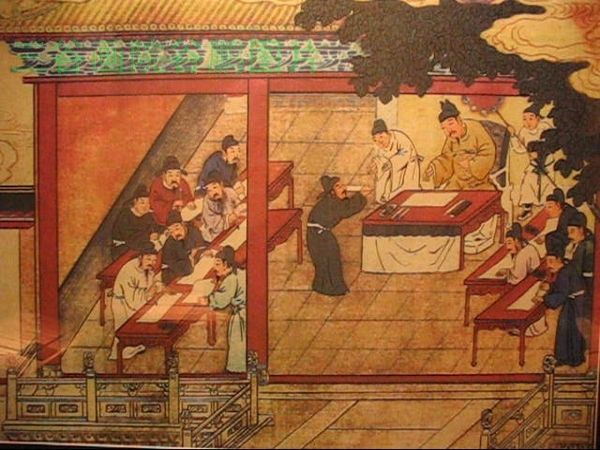

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the prestigious Imperial Academy (太学) operated with surprising flexibility. Unlike today’s regimented classrooms, Han scholars enjoyed no fixed graduation timeline or strict attendance policies. The system mirrored modern Western universities in its emphasis on self-directed learning—but with a distinctive twist.

Annual examinations called “岁试” (Yearly Tests) determined everything. In a ritual resembling carnival games, students literally “shot” arrows at bamboo slips containing questions—a practice called “设科射策” (Categorized Archery Examination). Passing meant government appointments; failing meant expulsion. With no daily oversight, a Han scholar’s workload depended entirely on personal ambition. Some thrived in this free environment, while others languished without structure.

The Tang Dynasty’s Examination Frenzy

By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), China’s education system had transformed into a high-pressure gauntlet. The Imperial Academy introduced frequent testing cycles: weekly (旬考), monthly (月考), quarterly (季考), and annual (岁考) assessments. Modern students enduring constant quizzes might recognize this relentless rhythm—proof that academic anxiety transcends centuries.

Tang administrators implemented strict expulsion policies. Three failed exams? Expelled. Nine years without graduation? Expelled. Excessive absences? Expelled. This unforgiving approach reflected the high stakes of Tang scholarship, where education served as the primary ladder to bureaucratic power.

Yet the Tang also pioneered student welfare measures. Their academic calendar included:

– “旬假”: A day off every 10 days (akin to weekends)

– “田假”: A 15-day farming break in May

– “授衣假”: Another 15-day hiatus in September for winter preparations

These proto-holidays acknowledged the physical and mental toll of constant study—an early recognition of burnout culture.

The Game-Changer: Imperial Examinations

The Sui and Tang dynasties’ creation of the imperial examination system (科举) revolutionized—and intensified—scholarly life. Now, every ambitious student crammed for the ultimate prize: civil service positions through standardized testing.

Memorization became survival. The Confucian “Thirteen Classics” demanded mastery of over 600,000 characters—texts and commentaries combined. As Ming Dynasty scholar Xie Zhaozhe warned: “Never study past midnight.” His advice reveals a culture of academic exhaustion, where burning the midnight oil was commonplace centuries before modern cram schools.

Private Academies: No Escape from the Grind

Outside the imperial system, private academies offered alternative education—but no respite. With fewer resources than government schools, these institutions often demanded greater student effort.

A typical day began at dawn, ending by afternoon. But “early dismissal” meant little relief. Students spent evenings memorizing texts, preparing for the same grueling exams as their elite counterparts. The dream of social mobility through scholarship kept lamps burning across China well into the night.

The Brutal Regimen of Qing Dynasty Royals

If common scholars suffered, Qing Dynasty (1636–1912) princes endured what historian Zhao Yi called “the strictest academic discipline in history.” Their schedule would break most modern learners:

– 4 AM: Arrive at school (before teachers)

– 5 AM: Manchu and Mongolian language lessons

– 7 AM–3 PM: Marathon sessions on Confucian classics and imperial histories

– 3 PM–5 PM: Military training (archery and horsemanship)

With only two 15-minute breaks daily and just five annual holidays, these child princes faced unparalleled pressure. The system produced exceptionally cultured emperors—but at what cost? Even on Lunar New Year’s Eve, classes merely ended slightly early.

Echoes Across Centuries

Today’s students might recognize their own struggles in these historical patterns: the stress of standardized testing, the debate over workload balance, even the concept of “gap days.” Ancient China’s educational extremes—from the Han’s flexibility to the Qing’s militarized discipline—reflect timeless tensions between achievement and well-being.

As modern education systems worldwide grapple with student mental health, these millennia-old experiences offer sobering perspective. The pursuit of knowledge has always demanded sacrifice—but history also shows the importance of balance, a lesson we’re still learning today.

No comments yet.