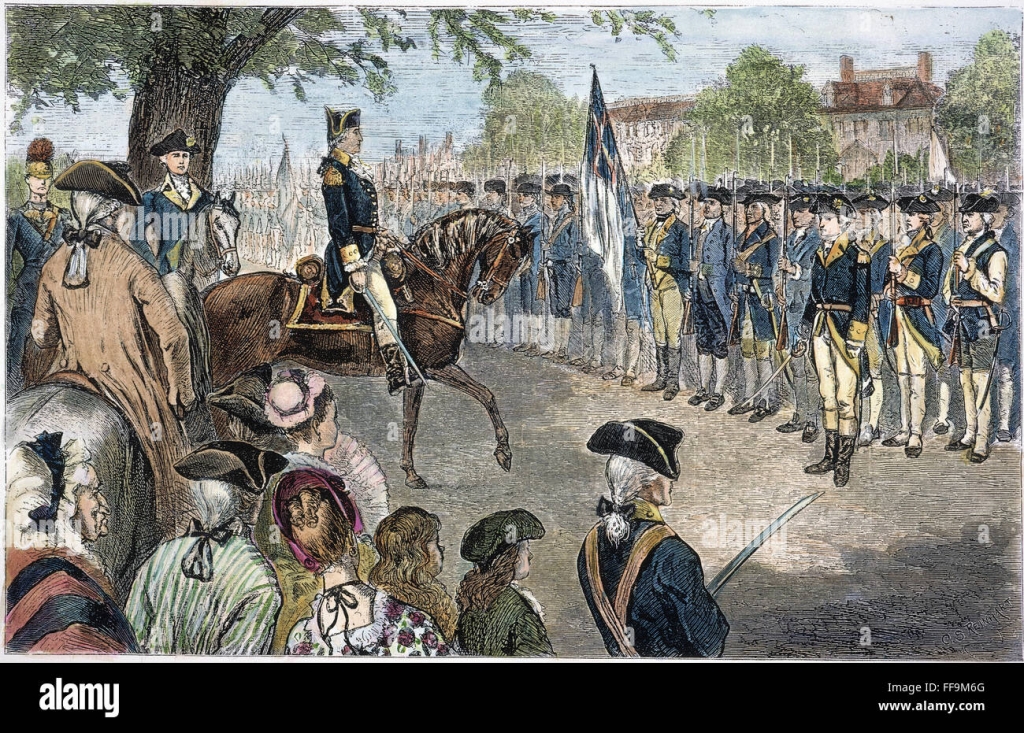

On July 2, 1775, George Washington arrived in Cambridge to take command of the Continental Army. It was a Sunday, a sacred day for New England Puritans, who observed it with strict devotion. Although Washington, a member of the Church of England, didn’t share their customs, he respectfully entered the camp in silence with his entourage. The soldiers were lined up in an open field, waiting for their new commander’s review. Washington gave a brief speech and sent them back to their posts. The sky was overcast, a light drizzle adding to the somber mood. As Washington stood among thousands of men, a deep loneliness set in—Mount Vernon felt like a distant dream. He was no longer the privileged gentleman of Virginia but a man facing the grim realities of war.

The soldiers, however, were immediately captivated by their new leader. Tall, handsome, and exuding an air of nobility, Washington looked every bit the commander they needed. Even his horse, Nelson, seemed to carry itself with extra grandeur. Years later, John Adams, with a hint of jealousy, would list Washington’s top qualifications: good looks, towering height, aristocratic demeanor, and graceful manners—qualities that seemed better suited for a Hollywood star than a general. But Adams had a point—Washington’s physical presence alone inspired confidence.

Washington’s first impression of his troops, however, was far from positive. The famous painting of Washington reviewing his army is highly flattering. The reality was a disorganized mess. There were no standard uniforms—some men wore rags, others had no shirts at all, having lost them in the Battle of Bunker Hill. Many were barefoot. The camp itself was chaotic, with tents haphazardly scattered, livestock running loose, and an overwhelming stench filling the air. A neat freak at heart, Washington nearly fainted at the sight. His first order? Clean up the camp, rebuild the tents properly, and, for heaven’s sake, wash their faces. It may have seemed trivial, but this simple act transformed the ragtag militia into something resembling an army.

Washington set up his headquarters at Harvard College, generously offered by President Samuel Langdon. Feeling guilty about displacing him, Washington soon moved into a vacant house, which would later become the home of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Despite the historical charm, Washington was quickly confronted with a harsh reality: the army’s condition was far worse than advertised. The Continental Congress had promised him 20,000 troops outside Boston. After subtracting the sick and wounded, there were only about 14,000 fit for battle. Worse, their weapons varied wildly—some had outdated muskets, some carried hunting rifles, and others wielded spears, bows, or even knives. The gunpowder situation was even more dire. Congress claimed they had 308 barrels; in truth, there were only 36, barely enough for each soldier to fire nine shots.

Why hadn’t the British attacked yet? Washington could only assume they had been intimidated by the Americans’ ferocity at Bunker Hill or simply unaware of their opponent’s dire state. So, Washington did what any smart leader would do—he bluffed. He paraded his troops, displayed his artillery, and projected an image of strength. At the same time, he implemented strict secrecy. Not even the Massachusetts Provincial Congress knew the truth about their supplies. He confided only in a select few, earning him the nickname “the genius of silence.” Washington’s commitment to secrecy would become legendary, shaping his leadership throughout the war and beyond.

Beyond logistical nightmares, Washington faced another challenge: regional tensions. New Englanders and Southerners didn’t get along, and Washington, a Virginian, was an outsider leading a predominantly New England army. To ease tensions, Congress appointed eight regional generals to serve under him. The most significant was Artemas Ward, the former leader of the Boston militia. Ward was deeply resentful of a Southerner taking command and showed little enthusiasm for cooperation. Another key figure was Charles Lee, a professional soldier from Virginia. Washington admired his experience, but Lee, in turn, saw himself as the more qualified leader and resented Washington’s appointment.

A breakthrough came in late July when 2,000 Virginians under Daniel Morgan arrived in Cambridge. Seeing his fellow Virginians brought Washington to the brink of tears. Soon after, Pennsylvania and Maryland troops also arrived, diversifying the army. But rather than unity, their arrival sparked new tensions. The well-dressed Virginians, with their fine shirts, stockings, and polished shoes, stood in stark contrast to the ragged New Englanders. Fights broke out, the most infamous being a massive brawl at Harvard Yard. Washington himself had to intervene, physically separating soldiers with his bare hands. His imposing strength stunned the men into obedience, proving his authority in an unexpected way.

Despite the small victories, Washington’s frustrations grew. One of his biggest headaches was the short-term enlistments. Most troops had signed up for only three or six months, meaning that just as they became trained, they were ready to go home. Washington pleaded with Congress for a standing army, but Congress, wary of tyranny, resisted. The fear was simple—if Washington had a permanent army, what would stop him from becoming a dictator? Only after much back-and-forth would Congress slowly extend enlistment terms, inching toward a real army.

Another challenge was the democratic nature of the militia. Unlike professional armies, Continental officers were elected, not appointed. Soldiers had little concept of following orders—they questioned commands, debated tactics, and resisted authority. Washington, accustomed to the hierarchical Virginia aristocracy, was appalled. How could he maintain discipline with a bunch of soldiers who acted like town hall voters?

These early struggles shaped Washington as a leader. He learned to balance diplomacy with authority, to navigate politics as skillfully as war. More importantly, he recognized that the Revolution wasn’t just about fighting—it was about forging a national identity. The disparate, squabbling colonies had to become a unified country. His first months in command were more than just a test of military strategy; they were a glimpse into the nation-building to come.

Legacy and Modern Lessons

Washington’s early days with the Continental Army reveal the messy, uncertain start of the American Revolution. His challenges—lack of supplies, regional divisions, and political constraints—mirror struggles seen in modern leadership. Building unity among diverse groups, maintaining morale under tough conditions, and projecting confidence in times of crisis are lessons that remain relevant today. Washington’s ability to adapt, strategize, and inspire would ultimately define his legacy, proving that leadership is as much about perseverance as it is about brilliance.

No comments yet.