Introduction

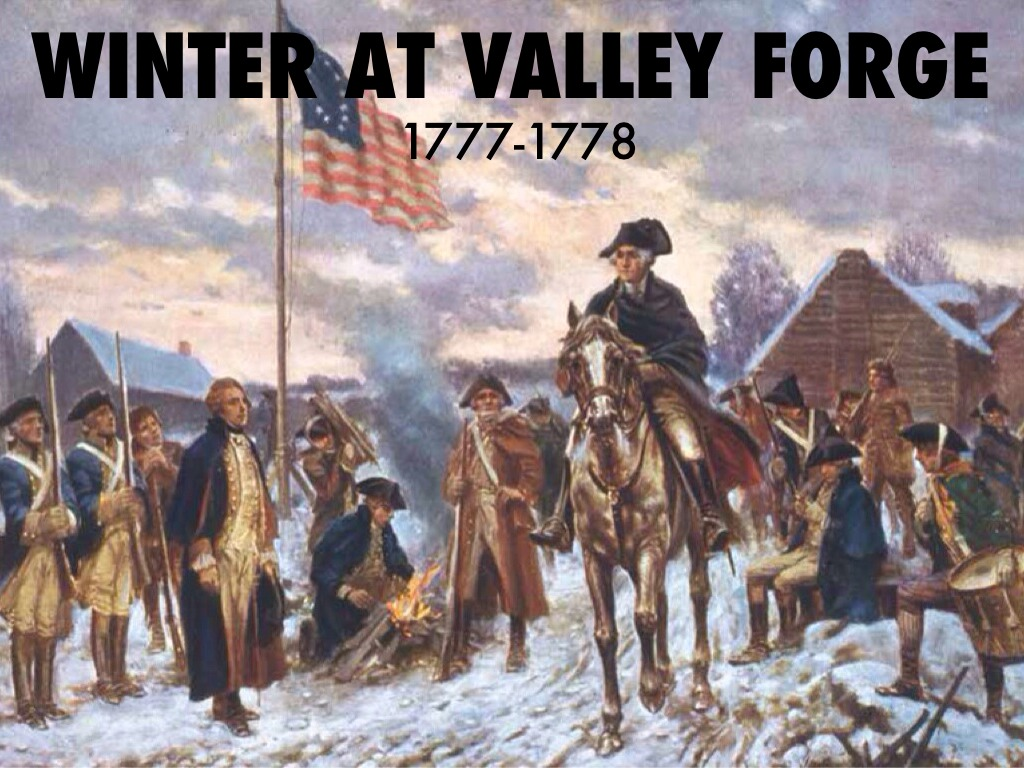

In December 1777, George Washington led his weary Continental Army into Valley Forge, a desolate stretch of land about 40 kilometers northwest of Philadelphia. After failed attempts to reclaim the city from British control, Washington sought a defensible location to monitor enemy movements while protecting the fledgling American government in York. Valley Forge was chosen for its strategic position, but it would become a forge in a different sense—one that tempered the resolve of the American Revolution.

A Winter of Desperation

The sight of the army arriving at Valley Forge was one of misery. Thousands of soldiers, many without shoes, left bloody footprints in the snow as they trudged toward what was supposed to be their winter encampment. Instead of barracks or supplies, they found only empty land. Washington had informed the Continental Congress about his plans, expecting at least the bare necessities to be prepared. But when the troops arrived, they found no food, no blankets, no winter clothing—nothing but an unforgiving wilderness.

While a famous painting inside today’s Valley Forge National Historical Park depicts Washington on his knees in prayer, historians debate whether he truly knelt in public. More likely, the burdened general sought divine assistance privately in his quarters. However, he also understood that prayer alone would not save his army.

The General’s Resolve

Washington was a man of action. He sent troops to the surrounding countryside to “borrow” supplies, instructed soldiers to fell trees for shelter, and personally oversaw the construction of log cabins. Within weeks, over a thousand crude huts dotted the valley, each accommodating about ten soldiers with triple-stacked bunks and a small fireplace. It was no paradise, but at least it was home.

Yet hunger remained an ever-present threat. To tackle the supply crisis, Washington appointed General Nathanael Greene as the army’s quartermaster. Greene, a shrewd political strategist, managed to establish a lifeline of food and materials, though just enough to keep starvation at bay. The question remained: why was an army fighting for American freedom left in such destitution while the farms surrounding Valley Forge overflowed with abundance?

The Weakness of the Confederation

The answer lay in the fractured nature of the American government. At this time, the United States was not a unified nation but a loose coalition of thirteen independent states. The recently drafted Articles of Confederation had created a government so weak that it could not enforce tax collection or military funding. Each state hoarded its resources, leaving Washington’s army—ostensibly fighting for all of them—begging for scraps.

With no authority to tax, the Continental Congress resorted to printing paper money, known as “Continental dollars.” Unlike European currencies backed by gold or silver, these notes were mere promissory slips with no tangible value. They depreciated at a staggering rate—what was worth a dollar in the morning could be nearly worthless by nightfall. As a result, local farmers preferred selling to the British, who paid in reliable gold and silver, rather than accepting Continental paper that might be worthless tomorrow. The irony was brutal: in British-occupied Philadelphia, enemy troops feasted and reveled, while just outside the city, Washington’s men starved.

Washington’s Leadership: The Anti-Dictator

Under such conditions, lesser men might have turned to authoritarianism. A different general—say, Napoleon Bonaparte or Oliver Cromwell—might have marched on Congress, seized power, and established a military dictatorship. Given the soldiers’ suffering, many would have cheered such a move. But Washington was different. He had no illusions about human nature and knew that revolutions often ended in tyranny. Instead of seizing power, he reinforced the principle that the military must remain subservient to civilian rule, no matter how incompetent that rule seemed.

Washington’s struggles at Valley Forge convinced him of one thing: America needed a stronger central government. His young aide, Alexander Hamilton, came to the same realization. While others in the revolutionary movement saw centralized power as synonymous with British oppression, Washington and Hamilton recognized its necessity. They admired Britain’s well-organized financial system, its stable currency, and its effective governance. If the United States was to survive, it had to learn from its former adversary.

The Turning Point

Amidst the despair, a glimmer of hope arrived: news of the American victory at Saratoga. Though the credit went to General Horatio Gates—Washington’s rival—the victory was significant enough to convince France to formally ally with the revolutionaries. With French supplies, funds, and military aid on the horizon, Washington’s army would not starve in vain. Moreover, the army itself was transforming. Under the guidance of Prussian officer Baron von Steuben, the ragtag troops of Valley Forge underwent rigorous drills and emerged in the spring as a disciplined, battle-ready force.

Legacy of Valley Forge

Valley Forge was not a battle—it was a trial by fire. The suffering endured there cemented Washington’s leadership and the resilience of the American cause. More importantly, it illuminated the flaws in America’s first attempt at self-governance. The Articles of Confederation would ultimately be replaced with the U.S. Constitution, creating the strong federal government Washington and Hamilton had envisioned.

Conclusion

Today, Valley Forge stands as a symbol not just of hardship, but of transformation. It was here that the United States truly began to form—not just as an idea, but as a functioning nation. And in a world where political division and economic instability still test democracies, the lessons of Valley Forge remain as relevant as ever: unity is forged through adversity, and strength is built on the willingness to adapt and learn from history.

No comments yet.