After eight grueling years of war, the American people had won their long-sought independence. But now came an even greater challenge: What kind of government should they establish? George Washington had returned to his farm, the Continental Army had disbanded, and there was no fear of dictatorship. But democracy and the rule of law—how would those work in practice? Where should the line between freedom and order be drawn? How much power should the central government have compared to the states? Could the people truly govern themselves?

In 1783, the newly formed United States was less of a country and more of a loose collection of independent states. There was no unified currency (each state printed its own money), no common legal system (each state had its own constitution), no standing army (each state had its own militia), no federal taxation (each state collected its own taxes), and no unified trade policies (each state set its own tariffs). Officially, the states were held together under the Articles of Confederation, a framework passed by the Continental Congress in 1777 and ratified in 1781. But in reality, the Confederation was a weak alliance—more of a “league of friendship” than a functioning national government.

The Weakest Central Government in History

Under the Articles of Confederation, the central government had no executive power, no judicial system, and barely any legislative authority. The Confederation Congress (formerly the Continental Congress) could make recommendations but had no power to enforce them. It could not levy taxes, regulate commerce, or compel states to cooperate. If a state refused to comply, the federal government had no real recourse—other than hoping for the best. In essence, it was a government designed to be weak, created out of fear that a strong central authority would lead to tyranny, just like the British monarchy they had fought to overthrow.

The states jealously guarded their independence, and many Americans saw a powerful central government as the first step toward oppression. Having just escaped the grasp of a king 3,000 miles away, why would they create another despot just a few hundred miles away? The logic was simple: the weaker the central government, the stronger the states—and, by extension, the people’s freedom.

Freedom Isn’t Free—It’s Chaotic

However, it didn’t take long for reality to set in. The weak government of the Confederation quickly led to a host of problems:

- No Respect on the World Stage – European nations, particularly Britain and Spain, scoffed at the new United States. Britain refused to withdraw its troops from American territory, while Spain closed off the Mississippi River, cutting off trade. With no military and no money, the Confederation could do little more than lodge complaints.

- Financial Crisis – The war had left America drowning in debt. The Confederation had borrowed money from France and the Netherlands, but since it had no power to tax, it couldn’t pay its loans. As a result, American bonds turned into near-worthless junk investments in European markets. The states, saddled with their own war debts, weren’t eager to contribute either. Creditors went unpaid, leading to economic instability and social unrest.

- Interstate Rivalries – Each state acted as its own sovereign nation, complete with trade barriers and competing interests. States imposed tariffs on each other’s goods, creating economic inefficiency. Merchants found it impossible to do business when they had to pay duties at every state border. The economy suffered, and businesses collapsed.

- Lawlessness and Rebellion – The most shocking failure of the Confederation came with Shays’ Rebellion in 1786-87. Massachusetts farmers, burdened by debt and high taxes, revolted against their state government. Led by Daniel Shays, a former Continental Army officer, the rebels shut down courthouses and attacked the state arsenal. The Confederation Congress had no power to raise an army, and when it asked the states for help, most ignored the call. The rebellion was finally put down—not by the federal government, but by a privately funded militia.

Shays’ Rebellion was a wake-up call. If one small group of farmers could nearly topple a state government, what was stopping the entire country from descending into chaos? It became clear that freedom without order was just as dangerous as tyranny.

The Birth of a New Constitution

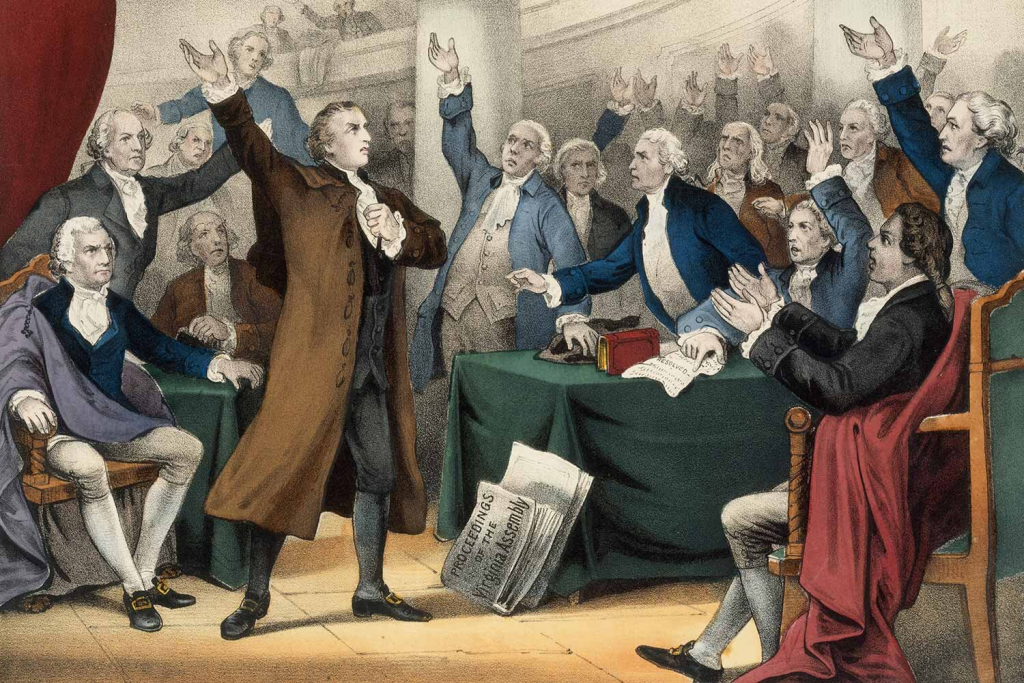

The failures of the Articles of Confederation made one thing clear: the United States needed a stronger central government. In 1787, leaders from across the states met in Philadelphia to fix the Articles—but instead, they scrapped them entirely and wrote a new Constitution. This new government would have a president, a national court system, and the power to tax, regulate commerce, and maintain order. It was a compromise between freedom and stability, designed to prevent both tyranny and anarchy.

The Legacy: Striking the Balance Between Freedom and Order

The struggle between state and federal power didn’t end in 1787—it remains a defining feature of American politics today. From debates over states’ rights in the Civil War to modern disputes over healthcare and education, the tension between local autonomy and national unity is still unresolved. The lesson of the Confederation is a timeless one: government must be strong enough to function but limited enough to preserve liberty. Finding that balance is the eternal challenge of democracy.

As America continues to evolve, the failures of the Confederation serve as a reminder that freedom alone is not enough—without structure, it collapses under its own weight. The early Americans learned that the hard way. Fortunately, they had the wisdom to correct course, creating a system that has endured for over two centuries.

No comments yet.