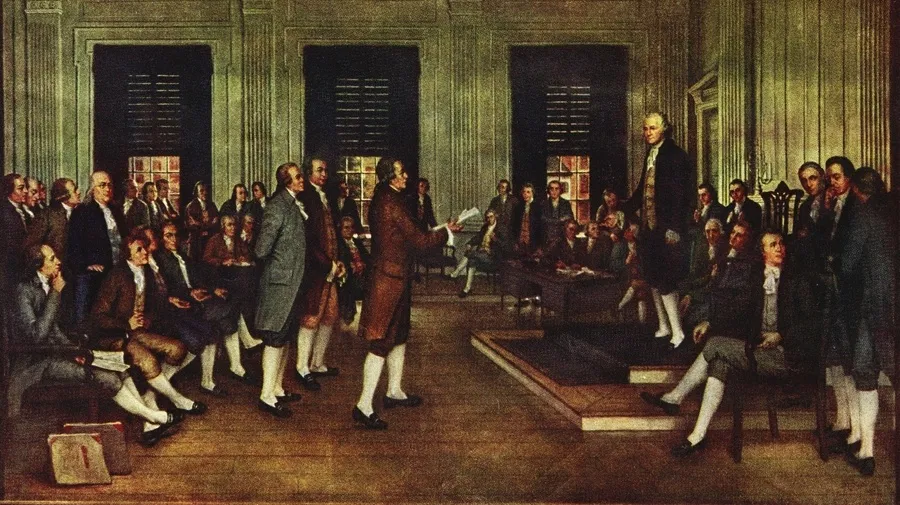

In the sweltering summer of 1787, as the Founding Fathers gathered in Philadelphia to draft the U.S. Constitution, one word loomed larger than any other: compromise. Without compromise, there would be no Constitution. But when it came to the three words that haunted the new nation—slavery—the cost of compromise was staggering. While the framers couldn’t foresee that their decisions would lead to the deaths of 600,000 Americans in the Civil War, they knew their choices were a stain on the Republic. Freedom was sacrificed for interest, and idealism bowed to reality. The three words that shamed the New World were: slavery, slavery, and slavery.

The Roots of Slavery: A Necessary Evil?

Slavery wasn’t born out of love or hate—it was born out of economic necessity. By 1787, the institution had been ingrained in the fabric of the New World for over a century. The South relied on enslaved labor for its agricultural economy, while the North profited from the slave trade. But as Enlightenment ideas spread, even the most hardened Southern slaveholders couldn’t ignore the moral contradictions. John Rutledge of South Carolina bluntly stated, “Religion and humanity have nothing to do with this question. Interest alone is the governing principle.”

Of the 55 delegates at the Constitutional Convention, about half owned slaves. George Washington himself brought three enslaved individuals to Philadelphia, seemingly unbothered by the irony of drafting a Constitution for freedom while holding people in bondage. Yet, the war had changed him. Influenced by abolitionist friends like Lafayette and Hamilton, Washington privately opposed slavery but took no public stand. Like many Founding Fathers, he balanced moral unease with economic reality.

The First Battle: Counting Slaves for Representation

The first major clash over slavery arose when delegates debated how to count enslaved people for congressional representation. Southern states wanted slaves counted as part of their population to increase their political power, while Northern states argued that if slaves were considered property, they shouldn’t be counted at all. Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, a fiery abolitionist, condemned slavery as “a curse from heaven” and pointed to the prosperity of free states compared to the poverty of slave states.

Southern delegates, however, were unmoved. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina argued that slavery was a global institution, practiced by ancient civilizations and modern nations alike. He warned that if the North threatened slavery, the South would walk away from the Union. Faced with the prospect of disunion, Northern delegates reluctantly agreed to the Three-Fifths Compromise, counting each enslaved person as three-fifths of a free person for representation and taxation purposes. This compromise gave the South disproportionate power in Congress, a decision that would haunt the nation for decades.

The Slave Trade: A 20-Year Reprieve

The next contentious issue was the slave trade. Southern states, particularly those in the Deep South like Georgia and South Carolina, relied on the importation of enslaved Africans to sustain their labor force. Northern states, while morally opposed to slavery, profited from the trade. Surprisingly, some Southern delegates, like George Mason of Virginia and Luther Martin of Maryland, opposed the slave trade, arguing it was immoral and economically harmful. But their opposition was less about morality and more about economics—Virginia and Maryland had a surplus of enslaved people and stood to profit from selling them to the Deep South.

In the end, the delegates struck another compromise: Congress would not interfere with the slave trade for 20 years, until 1808. This concession allowed the Deep South to continue importing enslaved people while giving the North time to phase out its involvement in the trade. The compromise was a bitter pill for abolitionists, but it kept the Union intact—for the time being.

The Fugitive Slave Clause: Freedom’s Betrayal

Perhaps the most insidious compromise was the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required Northern states to return escaped enslaved people to their Southern owners. This clause not only reinforced the institution of slavery but also undermined the growing abolitionist movement in the North. Enslaved individuals who had fled to free states were no longer safe; they had to reach Canada to secure their freedom. The clause was a stark reminder that the Constitution, while a groundbreaking document, was deeply flawed.

The Legacy: A Constitution Built on Contradictions

The compromises over slavery were necessary to create a unified nation, but they came at a profound moral cost. The Constitution’s framers knew they were embedding a contradiction at the heart of the Republic: a nation founded on the principle of liberty that enshrined slavery in its founding document. This contradiction would fester for decades, culminating in the Civil War.

Today, the Constitution’s compromises on slavery serve as a reminder of the complexities of nation-building. They highlight the tension between idealism and pragmatism, and the difficult choices leaders must make in the face of moral and political challenges. While the Constitution has been amended to correct some of its original sins, its legacy continues to shape debates over justice, equality, and freedom in modern America.

As we reflect on the Founding Fathers’ compromises, we’re reminded that progress is often messy and imperfect. The Constitution was not a perfect document, but it was a starting point—a framework for a nation that continues to strive toward its founding ideals. And in that striving, we find the true spirit of the American experiment.

No comments yet.