“A fox at fifty can transform into a woman. At a hundred, she becomes a beautiful sorceress, capable of bewitching people and foreseeing distant events. At a thousand, she ascends to the heavens as a celestial fox.”

— Xuanzhong Ji (Records from the Mysterious Realm)

The Chinese fox spirit, or huli jing (狐狸精), has long been associated with enchantment, seduction, and mystique. In folklore, these creatures often weave tales of love and deception, their cunning minds leading emperors astray and common folk into ruin. But was it always this way?

Digging through ancient texts, we find that the fox spirit’s image has undergone a remarkable transformation—one that reflects shifting cultural values and historical contexts. Once revered as a divine guardian, the fox spirit was gradually demonized into a seductive trickster. So, how did this happen? Let’s take a journey through time.

The Fox as a Divine Beast: The Sacred Guardians of Ancient China

Long before foxes were labeled as femme fatales, they were celestial creatures with divine significance. In Shan Hai Jing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), written over 2,000 years ago, the legendary Nine-Tailed Fox resided in the mythical land of Qingqiu (青丘).

This fox was no ordinary creature—it possessed immense spiritual power. Its cries mimicked those of a baby, luring humans close, only to devour them. But paradoxically, consuming the flesh of this fox granted immunity from all enchantments.

The Nine-Tailed Fox wasn’t merely a beast of legend; it was a powerful totem for ancient clans. The royal lineages of Tu Shan (涂山) and You Su (有蘇) traced their ancestry back to this mystical creature. Some even believed that Tu Shan, the wife of the legendary Emperor Yu (大禹), was a Nine-Tailed Fox in human form.

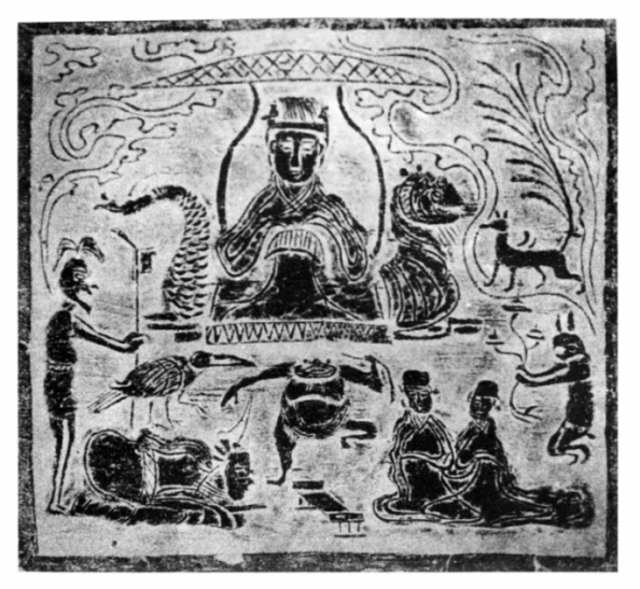

This divine fox was a harbinger of prosperity. According to The Book of Han and Records of the Grand Historian, white foxes and nine-tailed foxes were presented to emperors as auspicious omens, signaling an era of peace and good governance. In Han dynasty art, the fox was depicted alongside celestial beings like the Queen Mother of the West (西王母), reinforcing its divine status.

The Fox as a Deceiver: The Rise of the Femme Fatale

As time passed, particularly after the Han dynasty, the fox’s reputation took a dark turn. The idea that “old creatures gain spiritual power” (物老成精) led people to believe that aged foxes could shapeshift into humans—usually beautiful women with sinister intentions.

The most infamous of them all? Daji (妲己), the concubine of King Zhou of Shang (商纣王). According to Fengshen Yanyi (Investiture of the Gods), Daji was no ordinary woman but a thousand-year-old fox demon sent to corrupt the king and bring down the Shang dynasty. With her mesmerizing beauty and cruel delights—like forcing people to dance on burning bronze pillars—she became the ultimate symbol of fox-induced chaos.

From the Tang dynasty onward, foxes were frequently portrayed as seductive women in literature. They ensnared scholars, drained their vitality, and ultimately led them to ruin. By the Song dynasty, the term jiuweihu (九尾狐, “Nine-Tailed Fox”) had become an insult, referring to anyone—male or female—who was deceitful and manipulative.

In the Yuan and Ming dynasties, novels like Fengshen Yanyi solidified the fox demon’s association with treachery. The term huli jing (狐狸精) became a derogatory phrase used to describe women accused of using beauty to disrupt marriages and social order—a stigma that, surprisingly, persists in Chinese culture today.

The Fox as a Trickster and Lover: The Ambiguity of the Qing Dynasty

Not all fox spirits were malicious. In the Qing dynasty, Liao Zhai Zhi Yi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio) by Pu Songling reimagined fox spirits as complex beings—sometimes mischievous, sometimes benevolent, and often deeply emotional.

In these stories, fox spirits like Xiao Hong (小红) and Ying Ning (婴宁) were not just seductresses but also devoted lovers and protectors of those they cherished. Some helped humans, others sought love, and a few even practiced Daoist cultivation to achieve enlightenment.

One particular tale tells of a fox spirit standing under the moon, swallowing and refining a glowing pearl—an ancient Daoist method of inner alchemy. The message? Not all foxes took the path of deception. Some sought spiritual transcendence, just like humans.

Fox Spirits Today: Monsters, Muses, and Cultural Icons

From sacred guardians to demonized temptresses, the transformation of fox spirits in Chinese mythology mirrors shifting societal views on power, women, and the supernatural. But while classical texts villainized them, modern adaptations have embraced their complexity.

Today, fox spirits are everywhere in pop culture—anime, video games, and dramas portray them as powerful, intelligent, and even heroic. Shows like Legend of the White Snake and Painted Skin blur the lines between good and evil, love and deception, reminding us that fox spirits, like humans, walk the fine line between virtue and vice.

So, the next time you hear a story about a fox spirit, ask yourself: is she a villain, a lover, or a seeker of wisdom? The answer may not be as simple as it seems.

No comments yet.