When watching historical dramas, we often see ministers kneeling before the emperor and commoners kneeling before officials. But was kneeling always a sign of submission in Chinese history?

Kneeling Was Just a Way to Sit

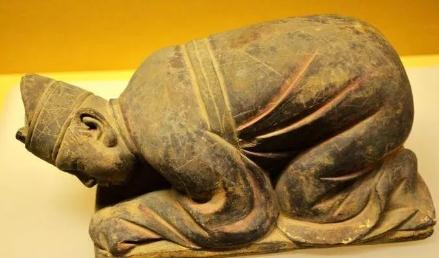

In ancient China, kneeling was not originally a ritual of submission but simply a natural sitting posture. Before the widespread use of chairs, people sat on mats placed on the floor. The common posture was kneeling with the buttocks resting on the heels, a position similar to the modern Japanese “seiza.” This posture had no hierarchical connotation—it was just how everyone, from peasants to nobles, sat.

During the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), when someone wanted to show respect, they would lean forward from their kneeling position. If their hands touched the ground, this became a formal bow. Even kings knelt and bowed to their ministers as a sign of mutual respect. A historical record in The Strategies of the Warring States describes how King Zhao of Qin kneeled and respectfully addressed his advisor Fan Ju, who then bowed back. This mutual etiquette remained unchanged through the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

The Rise of Chairs and the Change in Kneeling

A major shift happened during the Five Dynasties (907-960 CE) and the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) when high-back chairs became common. As people stopped kneeling in daily life, kneeling transformed into a deliberate act reserved for special occasions. It became a symbolic gesture rather than a casual sitting posture. However, even in the Song Dynasty, ministers typically stood in the emperor’s presence instead of kneeling, using a hand gesture called “yibai” to show respect.

The Mongols and the Institutionalization of Kneeling

Everything changed under the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 CE), ruled by the Mongols. Kneeling was institutionalized as an act of submission, reflecting the Mongol worldview that officials were subordinates rather than respected advisors. Ministers were required to kneel before speaking to the emperor, solidifying kneeling as a mark of inferiority rather than mere etiquette. The following Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) not only retained this practice but intensified it. Emperor Hongwu (Zhu Yuanzhang) mandated that officials kneel not only before the emperor but even before their superiors within the bureaucracy. By the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 CE), kneeling was no longer enough—officials had to kowtow, repeatedly touching their heads to the ground. Some even bribed court eunuchs to position them over hollow tiles, ensuring a loud “thud” when their foreheads hit the floor.

Kneeling, Diplomacy, and the Clash of Cultures

The Qing Dynasty extended kneeling rituals to foreign diplomacy, creating tensions with Western envoys. The British ambassador George Macartney, who visited China in 1793, refused to perform the kowtow to Emperor Qianlong, arguing that as a representative of the British king, he should not kneel. This seemingly minor protocol dispute symbolized a broader clash between China’s hierarchical worldview and the Western concept of diplomatic equality. Some historians argue that this cultural misunderstanding contributed to the growing rift that ultimately led to the Opium War (1839-1842).

The Legacy of Kneeling

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty, kneeling as a formal custom was abolished, surviving only in familial rituals such as paying respects to parents or ancestors. Yet, as some critics argue, while physical kneeling disappeared, psychological submission persisted. Even in modern times, remnants of this hierarchical mindset can still be found in certain social and political attitudes.

The evolution of kneeling in China reflects deeper shifts in political power and societal values. From an everyday sitting posture to a symbol of submission, kneeling’s transformation mirrors the rise of autocracy and the erosion of mutual respect in governance. Understanding this history reminds us that even small gestures can carry profound meanings—and that true respect should be mutual, not one-sided.

No comments yet.