In today’s world, splurging on a lavish meal at a fine restaurant might cost you a few hundred or even thousands of yuan, depending on your tastes. But have you ever wondered how much our ancestors paid when dining out? Were ancient banquets truly extravagant or surprisingly thrifty? Let’s take a step back in time and dig into the restaurant culture of ancient China, starting from the bustling cities of the Song dynasty and moving through the lavish halls of Qing dynasty mansions.

Street Food for a Song: The Common Man’s Meal

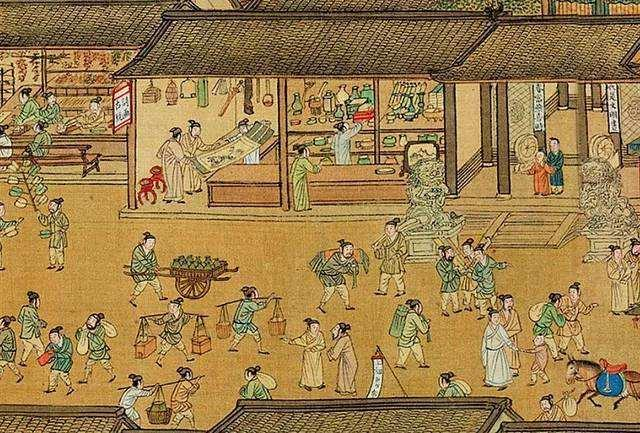

To get a sense of how affordable eating out was in the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), we begin with the humble street food stalls that lined the streets of the capital, Tokyo Bianliang — now known as Kaifeng.

According to the classic chronicle Dongjing Meng Hua Lu (Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital), you could grab a serving of fried fish, duck, stir-fried chicken or rabbit, or even a hearty soup called fengen for just 15 wen — a copper coin currency in use during the period. Adjusted to modern equivalents (roughly 0.8 RMB per wen), that’s about 12 yuan per dish.

Yes, a full meal on the streets of Bianliang could cost less than your average bowl of noodles in modern-day Beijing. Poet Lu You wrote in his Jian Nan Shi Gao (Poems from the South of the Sword) that a countryside tavern meal with a few side dishes and local wine could be had for 100 wen — equivalent to around 80 yuan today.

These “fly restaurants” or cangying guan were the equivalent of modern-day hole-in-the-wall joints. Affordable, simple, and accessible — the working class’s answer to a quick, hot meal after a long day.

A Literati Luncheon: Mid-Tier Dining for Scholars

Of course, not everyone dined on the street. The refined world of scholars and low-ranking officials had its own culinary preferences and budgets. In Dongpo Zhi Lin, Su Shi (Su Dongpo), a famous Song poet and statesman, described casual gatherings with fellow scholars. A small get-together for “two or three gentlemen” might cost 500 wen — the modern equivalent of around 400 yuan.

Meals in this price range were served at mid-tier restaurants — the ancient equivalent of today’s mid-range bistros or themed eateries. You’d expect table service, more varied and refined dishes, and a touch of elegance. For the educated class, dining was not just about food; it was also about poetry, conversation, and social bonding.

Going Grand: Banquets in High-End Restaurants

If you really wanted to impress, then the top-tier establishments in cities like Lin’an (modern Hangzhou), the Southern Song capital, were the places to be. As recorded in Du Cheng Ji Sheng (A Record of the Prosperity of the Capital), a meal in a fancy restaurant could easily cost 5,000 wen — roughly 4,000 yuan today.

Such places catered to the elite: wealthy merchants, government officials, or those hoping to become one. These restaurants had private rooms, elaborate menus, live entertainment, and top-quality ingredients — think of it as a Michelin-starred experience in silk robes.

The Price of Courtship: When Love Breaks the Bank

It turns out that romance has always come with a hefty price tag. In Jin Yong’s classic novel The Legend of the Condor Heroes, set in the Southern Song period, protagonist Guo Jing treated the clever and charming Huang Rong to a luxurious meal in an upscale restaurant. The damage? 19 taels of silver — equivalent to over 30,000 yuan in today’s terms.

This extravagant meal highlights two key things. First, that fine dining in the Song dynasty could be outrageously expensive if you pulled out all the stops. Second, some things never change: trying to impress a date often leads to a lighter wallet.

From Dream Gardens to Imperial Feasts: The Qing Dynasty’s Table

Fast-forward to the Qing dynasty and step into the world of The Dream of the Red Chamber (Hong Lou Meng), one of China’s greatest literary classics. In this richly detailed novel, the rustic Liu Laolao visits the aristocratic Rongguo Mansion and is treated to a luxurious crab feast at the fabled Grand View Garden (Da Guan Yuan). The meal reportedly cost 20 taels of silver, which would be equivalent to about 14,000 yuan today.

Keep in mind: this wasn’t a public restaurant but a private home banquet — and the amount only covered the ingredients. Such figures underline just how wealthy the Rongguo household was, and how massive the gap was between elite and peasant families.

Liu Laolao’s astonishment — “This meal costs as much as a whole year’s expenses for a farming family!” — says it all.

Government Dining: When the Bill Isn’t Yours to Pay

The most jaw-dropping bills, however, came not from nobles or poets, but from officials — especially when the government footed the bill.

During the reign of the Daoguang Emperor (1820–1850), the official Zhang Jixin, who held the prestigious position of Grain Circuit Commissioner in Shaanxi (a role roughly equivalent to a modern vice governor), regularly hosted banquets for visiting dignitaries. Each official banquet reportedly cost over 2,000 taels of silver — that’s around 700,000 yuan today!

According to his meticulous records, each event featured:

- Five top-tier tables for high-ranking guests

- Fourteen mid-tier tables for others

- Luxury ingredients like bird’s nest, roasted meats, shark fin, sea cucumber, live fish, white eel, and deer tail

Breaking it down, that’s around 30,000–40,000 yuan per table, enough to rival today’s top corporate banquets. And yes — the liquor flowed freely. As a tongue-in-cheek comparison, just five bottles of Moutai per table would already burn through 10,000 yuan.

This wasn’t mere indulgence; it was political theater, status display, and social strategy rolled into one. And it was all paid by the state.

More Than Just a Meal

What these examples reveal is that dining in ancient China was far more nuanced than one might imagine. Yes, you could enjoy a full meal on the street for the price of a cup of bubble tea. But dining could also become an elite performance of wealth and taste, with banquets so lavish they could feed entire villages for months.

These stories are more than culinary trivia. They reflect social hierarchies, economic conditions, and even romantic customs of their time. Whether it was a scholar savoring tofu and poetry or an official flaunting shark fin soup to seal alliances, meals were never just meals — they were statements of class, power, and affection.

So next time you complain about a pricey night out, just remember — a Southern Song lover once dropped thirty grand on a dinner date. Some traditions, it seems, are timeless.

Curious to Learn More?

Explore how food shaped ancient Chinese diplomacy, literature, and everyday life — from Tang dynasty teahouses to Qing dynasty imperial kitchens. Ancient dining wasn’t just about taste, but identity.

Let your next meal be a bite into history.

No comments yet.