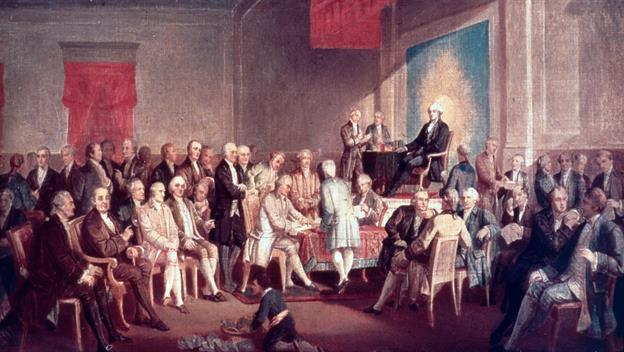

When the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788, it established a strong federal government, but it lacked one crucial element: explicit protection of individual rights. This glaring omission ignited a fierce debate between the Federalists, who supported the new Constitution, and the Anti-Federalists, who feared that without a Bill of Rights, the government could trample on personal freedoms.

The Federalists, including Alexander Hamilton, argued that the Constitution already limited the government’s powers, making a Bill of Rights unnecessary. However, their opponents were not convinced. The Anti-Federalists pointed to clauses like the “Necessary and Proper” and “Supremacy” clauses, which they believed gave the federal government too much power. They feared that without explicit guarantees, individual rights could be overridden by Congress or ignored by the Supreme Court.

This concern was echoed by prominent figures like the French aristocrat Marquis de Lafayette, who found it unthinkable that a republic could lack a Bill of Rights. Even Thomas Jefferson, then serving as the U.S. Minister to France, wrote lengthy letters to his friend James Madison, arguing that a Bill of Rights was essential to safeguard personal liberties against potential government overreach.

The debate reached its peak when several states, including North Carolina and Rhode Island, outright refused to join the Union unless a Bill of Rights was added. Under mounting pressure, James Madison, initially skeptical of the necessity of such amendments, took on the task of drafting what would become the first ten amendments to the Constitution. In 1789, Congress approved twelve proposed amendments and sent them to the states for ratification. By December 15, 1791, ten of them had been approved, officially becoming the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights enshrined fundamental freedoms such as freedom of speech, religion, and the press (First Amendment), the right to bear arms (Second Amendment), and protections against unreasonable searches and seizures (Fourth Amendment). It also included safeguards for those accused of crimes and limits on the federal government’s power.

One of the key principles behind the Bill of Rights was the idea that democracy itself could become oppressive. While dictatorships impose the tyranny of a single ruler, democracies risk the tyranny of the majority. The Bill of Rights aimed to prevent such oppression by ensuring that individual freedoms could not be easily overridden by popular vote or political maneuvering.

This concern was not just theoretical. History has shown that democratically elected governments have committed grave injustices, such as the persecution of minorities. The rise of Nazi Germany in the 1930s serves as a stark reminder that majoritarian rule does not always protect individual freedoms. In the U.S., legal battles over civil rights, free speech, and religious freedom continue to test the resilience of the Bill of Rights.

One of the most famous cases involving the First Amendment was the 1947 Supreme Court case Everson v. Board of Education, which established the principle of “separation of church and state.” Another key case, New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), reinforced the protection of freedom of the press, even when criticizing public officials. These rulings demonstrate how the Bill of Rights remains a living document, shaping American law and society to this day.

Even now, the Bill of Rights plays a crucial role in debates over privacy, gun control, free speech, and religious freedom. While interpretations may evolve, its core purpose remains the same: to protect individual liberties against government overreach. As Americans navigate new challenges in an ever-changing world, the Bill of Rights stands as a reminder that freedom is not just granted—it must be actively defended.

No comments yet.