In the realm of ancient Chinese daily life, comfort and relaxation were just as important as they are today. The evolution of seating and sleeping furniture tells a fascinating story of cultural shifts, technological advancements, and social status. Let’s take a journey through history and explore how our ancestors sat, lounged, and slept.

The Birth of the Bed

The earliest known sleeping furniture dates back to the Banpo culture, a matriarchal society during the Neolithic period. Their primitive “beds” were essentially raised earthen platforms, much like today’s kang (heated brick bed) found in northern China. By the Shang and Zhou dynasties, the structure of beds became more refined, marking the establishment of their classic form.

The Rise of the Ta (榻)

While beds were designed for nighttime rest, the need for daytime lounging led to the invention of the ta (榻). Contrary to modern usage, where “bed” and “ta” are sometimes used interchangeably, ancient China had a clear distinction between them. The ta originated from woven mats that were traditionally spread on the ground. As noble classes sought greater comfort and prestige, they developed raised wooden platforms—thus giving birth to the ta. Unlike beds, these were smaller, portable, and commonly found in living areas.

One famous phrase, “卧榻之侧,岂容他人酣睡” (“How can one tolerate another sleeping beside their ta?”), is often misunderstood. Many assume the ta in this phrase refers to a bed, but in reality, it was more of a lounging couch.

The Xi Ju Zhi (席居制): Life on the Floor

Before chairs became common, the predominant way of sitting in China was the xi ju zhi (席居制), or “mat-sitting culture.” People sat or knelt on thick woven mats made of straw or bamboo. Over time, thicker and softer variations called yanxi (筵席) emerged, which later influenced Japanese tatami flooring.

The Arrival of Chairs: A Foreign Influence

By the mid-Tang Dynasty, Chinese furniture underwent a major shift, thanks to cultural exchanges with northern nomadic tribes. These groups used portable folding stools, known as hu chuang (胡床), or “barbarian beds.” Despite their name, these were actually early versions of chairs rather than beds. This innovation gained popularity among Chinese elites and eventually led to the widespread adoption of chairs.

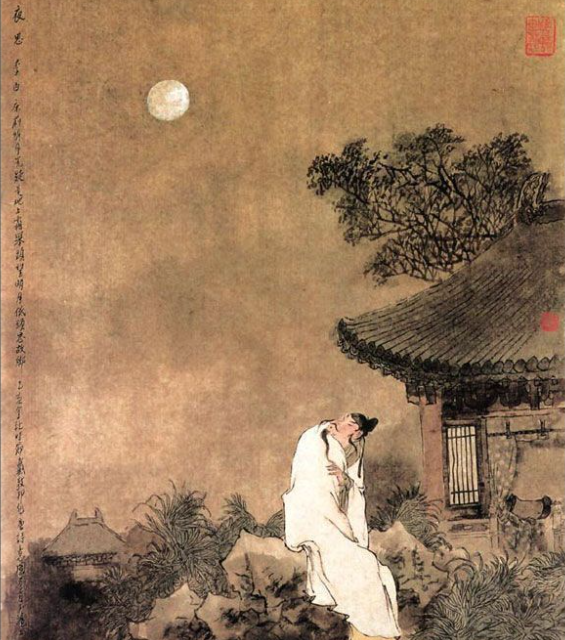

Interestingly, Li Bai’s famous poem, Jing Ye Si (《静夜思》), contains the line “床前明月光” (“Moonlight before my bed”). Many assume “chuang” (床) here refers to a sleeping bed, but it could actually have been a hu chuang, meaning Li Bai might have been sitting on a portable chair while gazing at the moon.

The Song Dynasty Boom: Chairs for Everyone

By the Song Dynasty, the evolution from hu chuang to full-fledged chairs was complete. The taishi yi (太师椅), or “Grand Chancellor’s Chair,” became a symbol of authority and power. Interestingly, it is said to have ties to Qin Hui (秦桧), a controversial historical figure. By this time, chair-sitting had entirely replaced mat-sitting among the upper and middle classes.

Ming and Qing Dynasties: The Rise of Lohan Beds

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, furniture became increasingly sophisticated. The luohan chuang (罗汉床), or “Lohan bed,” was a hybrid between a bed and a ta. It featured low railings, allowing for sitting, reclining, and sleeping—much like today’s sofas. Meanwhile, beds evolved into fully enclosed structures, resembling miniature rooms. The babu chuang (拔步床), a canopy bed with intricate wood carvings, became a status symbol for wealthy families.

Furniture and Social Etiquette

Furniture in ancient China wasn’t just about comfort—it was also a marker of social hierarchy. During the Han Dynasty, only high-status individuals had the privilege of using ta. One famous anecdote tells of Chen Fan (陈藩), a high-ranking official, who reserved a special ta for his esteemed friend Xu Zhi (徐稚). He would hang the ta on the wall when Xu Zhi was away and take it down only when he visited. This tradition inspired the modern term xia ta (下榻), which now means “to stay at a place as a guest.”

Even today, echoes of these traditions remain. In northern China, it is customary to invite guests to “sit on the kang” (上炕坐), a gesture of warm hospitality that harks back to ancient customs.

Conclusion: Ancient Comfort, Modern Influence

The evolution of sitting and sleeping furniture in ancient China reflects broader cultural, technological, and societal changes. From sleeping on raised earth platforms to lounging on ta, and finally embracing chairs, each transition marks a shift in both lifestyle and aesthetics. The Japanese tatami, modern sofas, and even our understanding of social etiquette all bear traces of these ancient traditions.

Next time you lounge on your couch, take a moment to appreciate how furniture has shaped the way we live—both in ancient times and today.

No comments yet.