“Mother, I am considering killing off Sherlock Holmes… just to be done with him. He’s taking up too much of my time.”

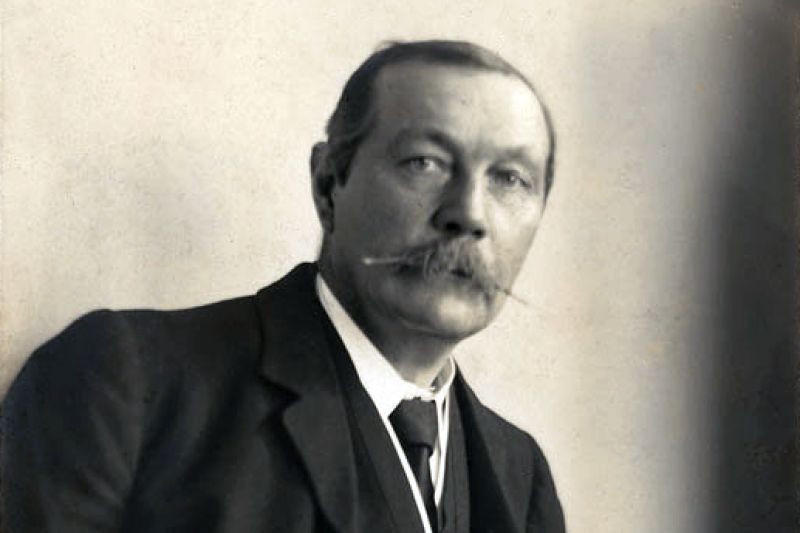

No, these words weren’t spoken by Dr. Watson in a fit of rage after another condescending remark from Holmes. They were written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—the very man who created the world’s most famous detective.

The response from his mother? A firm NO! Absolutely not! Don’t even think about it!

But Doyle, despite maternal objections, was determined. In 1893, he threw Sherlock Holmes off the Reichenbach Falls, taking down the infamous Professor Moriarty with him. He thought he was free.

He was very, very wrong.

When Fiction Becomes Reality

The reaction to Holmes’ death was nothing short of chaos. Thousands of outraged Britons took to the streets in protest, flooding the publishing house with angry letters. Readers mourned as if a real person had died. Some even wore black armbands in mourning. One furious reader allegedly canceled his subscription to The Strand Magazine and sent a letter calling Doyle a “brute.” Even Queen Victoria herself was reportedly troubled by the public outcry.

This was arguably the most dramatic reaction to a fictional character’s demise in literary history.

The Accidental Father of Detective Fiction

So why did killing off Sherlock Holmes cause such an uproar? Simple: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes was the 19th-century equivalent of today’s biggest hit TV series. Doyle’s work was translated into 57 languages, adapted into hundreds of films and TV series (292 and counting!), and turned detective fiction into a worldwide phenomenon.

Before Sherlock, detective stories were barely a thing. After him, they became a genre.

And every great detective since? They all follow the same formula Doyle created: a brilliant but eccentric genius paired with a loyal, slightly less insightful sidekick.

- Hercule Poirot has Captain Hastings.

- Judge Bao has Gongsun Ce.

- Di Renjie has Yuanfang.

- Even Detective Conan got its name as a tribute to Doyle!

Somerset Maugham once said:

“No detective story has ever enjoyed the same fame as the ones written by Conan Doyle.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. Doyle was, in many ways, the father of detective fiction.

An Unhappy Childhood, A Writer in the Making

Ironically, Doyle spent his life trying to escape that title. But fate had other plans.

Born in 1859 in Edinburgh, Scotland, Doyle grew up in a troubled household. His father, Charles Doyle, was a talented artist but an alcoholic with severe mental illness. His violent outbursts and financial irresponsibility cast a shadow over Doyle’s childhood.

To escape reality, young Arthur turned to the only source of comfort he had: his mother’s stories. She filled his mind with tales of knights and adventure, unknowingly planting the seeds of a storyteller.

At nine, Doyle was sent to a Jesuit boarding school in England. His teenage years were spent away from home, shaping his resilience and independence.

The Real Sherlock Holmes

In 1876, Doyle entered the University of Edinburgh to study medicine. He wasn’t exactly the best student, but he did meet someone who would change his life: Dr. Joseph Bell.

Bell wasn’t just a professor—he was a walking, talking Sherlock Holmes prototype. His incredible powers of deduction allowed him to diagnose patients within seconds, simply by observing them.

Doyle once recalled an astonishing moment in class:

Bell took one look at a new patient and said:

“You were in the army, stationed in Scotland, recently discharged from Barbados.”

The patient, shocked, confirmed every word.

Bell turned to his students and explained:

“The man’s polite but didn’t remove his hat—an old army habit. He still follows it, meaning he left the army recently. His authoritative posture suggests he was a sergeant. His illness is elephantiasis, common in the West Indies, which is why I deduced he had been in Barbados.”

Doyle wasn’t the best medical student, but he was a great note-taker. And when he finally put pen to paper years later, he transformed Bell into his greatest creation: Sherlock Holmes.

The Reluctant Detective Writer

Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, was published in 1887. It became an instant sensation. By the time The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes was serialized, his books were selling half a million copies.

Readers were obsessed.

People wrote letters to Doyle asking for Holmes’ actual address in London. When a character in a Holmes story died, real people wore mourning bands. When Holmes “retired” to Sussex to raise bees, fans asked Doyle for his beekeeping tips.

Holmes had become more than fiction—he was real in the minds of the public.

And Doyle? He was growing sick of him.

Despite the fame and fortune, Doyle had loftier ambitions. He wanted to write serious historical novels, to be recognized as a real literary figure. But no matter what he wrote, readers only cared about one thing: more Sherlock.

So he did what any rational writer would do—he killed his most famous character.

Sherlock’s Not-So-Final Death

Doyle knew what he was doing when he wrote The Final Problem. He once admitted:

“I will make Holmes fall to his death, even if my bank account falls with him.”

And it did.

The Strand Magazine lost 20,000 subscribers overnight. Fans were devastated. Doyle, meanwhile, moved on. His father passed away, his wife was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and for eight years, he focused on writing “serious” literature.

But the world didn’t forget.

In 1901, Doyle tested the waters by writing The Hound of the Baskervilles, a prequel featuring Holmes. It was an instant hit. Readers wanted more.

By 1903, Doyle surrendered. He wrote The Adventure of the Empty House, bringing Holmes back from the dead with a flimsy explanation: he faked his death.

And just like that, Sherlock was back.

For the next two decades, Doyle continued writing Holmes stories. Until his death in 1930, he never truly escaped the detective he had once tried to kill.

The Man Who Lived Forever

When Doyle passed away, The Daily Herald wrote:

“Conan Doyle is dead. But Sherlock Holmes is immortal.”

And they were right.

In Edinburgh, the city didn’t erect a statue of Doyle. Instead, they built one for Sherlock Holmes.

And in 2002, the Royal Society of Chemistry awarded Holmes an honorary fellowship—an honor usually reserved for Nobel Prize winners.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had spent his life trying to escape Sherlock Holmes.

But in the end, Holmes was the one who truly outlived his creator.

No comments yet.