If you’ve ever fantasized about time-traveling to ancient China, slipping into a flowing hanfu, and striking up a convo with Confucius over tea—well, you might want to hit pause. While it’s true that ancient Chinese folks did speak in a form of everyday language much like ours, actually understanding them could be a whole different story. Let’s unpack this fascinating linguistic journey and discover why chatting with your Tang Dynasty doppelgänger might not go as smoothly as you think.

Did Ancient Chinese Speak in “Thee, Thou, and Thus”?

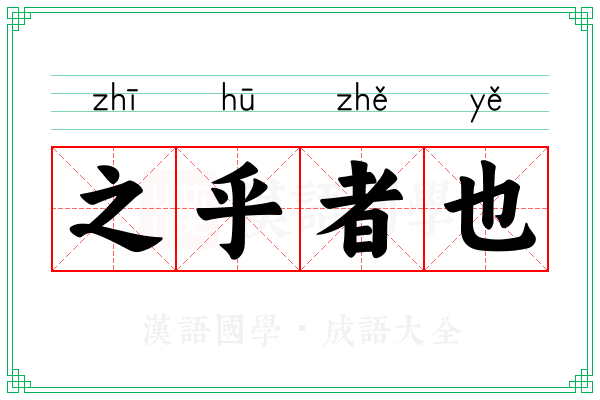

Many people assume that all ancient Chinese conversations sounded like classical prose—stuffed with “之乎者也” and incomprehensible to modern ears. But here’s the twist: ancient folks didn’t talk like that at all in their daily lives.

Classical Chinese, or wenyanwen, was primarily used in writing. In the Spring and Autumn period, there wasn’t much difference between spoken and written language. But by the time of the Warring States, wenyanwen became fossilized—while spoken Chinese kept evolving, influenced especially by waves of migration and cultural mixing (thanks, nomadic tribes!).

By the Tang Dynasty, the split was clear. People spoke in baihua (colloquial Chinese) but wrote in wenyanwen. Why not just write how they talked? Well, ancient writing materials—bronze, bamboo slips, silk—were crazy expensive. So, people had to be economical with words. Classical Chinese was the ultimate shorthand. Imagine fitting a 100,000-word book onto 30 pounds of bamboo! Talk about a workout.

Why Did Wenyanwen Stick Around for So Long?

Even after papermaking and printing took off in the Han, Tang, and Song dynasties, wenyanwen didn’t disappear. It was about prestige. Writing in classical Chinese showed you were educated—a scholar, not just one of the “masses.” It became the language of the elite, kind of like using Latin in medieval Europe.

But change was brewing.

The Song Dynasty saw the rise of huaben (storytelling scripts), blending oral language and literature—an early form of baihua fiction. These stories were accessible, lively, and relatable. The four great classical novels—Journey to the West, Dream of the Red Chamber, Water Margin, and Romance of the Three Kingdoms—are all baihua masterpieces. That’s why modern students breeze through them but struggle with the all-classical Records of the Grand Historian.

By the Ming and Qing dynasties, spoken Chinese in literature became the norm. Even emperors got in on the act. Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang, never known for eloquence, once issued a decree in plain language:

“Tell the people to get their knives ready. If those pirates show up—just kill them.”

Brutal, yes. But even a 10-year-old today could understand it.

The Qing’s Yongzheng Emperor was known for writing affectionate notes in plain Chinese to his officials. “I am just this kind of guy,” he once wrote. And yes, he even used “你好吗?”—the modern “How are you?”

But Wait—Could You Actually Understand Them?

So far, so good? Not so fast. Even if they spoke baihua, their pronunciation was nothing like modern Mandarin.

Linguists divide historical Chinese pronunciation into three broad periods: Old Chinese (Shang to Han), Middle Chinese (Southern and Northern Dynasties to Tang), and Early Modern Chinese (Song to Qing). These sound systems were vastly different—not just from today’s Mandarin, but from each other.

Take the famous line from The Book of Songs: “青青子衿” (Green, green your robe). Depending on the era, it might have sounded like:

- Old Chinese: cen cen cilumu kelumu

- Middle Chinese: ceng ceng ci ginmu

- Early Modern Chinese: cing cing zi gin

Confused? Sounds more like Klingon than Chinese, right?

This major shift was partly due to nomadic tribes settling in the north and influencing Chinese phonetics. Some southern dialects—like Cantonese, Hokkien, and Shanghainese—preserve bits of these older pronunciations, which is why speakers of these dialects sometimes find Japanese or Korean surprisingly familiar. Even the old “entering tone” (入声), long gone in Mandarin, survives in southern speech and classical Chinese poetry.

So How Do We Know What Ancient Chinese Sounded Like?

No, ancient China didn’t have recording devices. But they did have something ingenious: fanqie. This was a system of phonetic annotation using known characters to approximate the pronunciation of unknown ones. For example, the word 峰 (feng) would be notated as “房生切”—using “房” for the initial sound f and “生” for the final sound eng.

With massive dictionaries like the Qieyun from the Sui Dynasty, linguists have been able to reconstruct Middle Chinese pronunciation. Old Chinese is trickier—it often involves comparing related languages like Tibetan and using rhyme schemes from ancient poetry. It’s a bit like reverse-engineering a lost melody by studying old instruments and sheet music.

Culture, Identity, and a Whisper from the Past

Language is more than a tool—it’s a vessel for culture, identity, and memory. The journey from wenyanwen to baihua, and from archaic sounds to modern Mandarin, mirrors China’s evolution: from a feudal patchwork to a centralized empire, from scholar-gentry to public readership.

Modern Mandarin is easier, sure. But the echoes of the past are still with us—in idioms, in proverbs, and in poetry. Understanding this linguistic history isn’t just about geeking out over phonetics (though that’s fun too). It’s about seeing how people thousands of years ago thought, spoke, and lived.

So, next time you read a Tang poem or hear a line in Cantonese that feels oddly familiar, remember: the past is never really silent—it just speaks in an older voice.

No comments yet.