When we think of ancient Chinese rulers, the first image that comes to mind is often one of mighty emperors who brought glory and peace to their lands. However, history also reveals a darker side to these leaders—one where paranoia and betrayal led to a brutal culture of eliminating perceived threats. One phrase that echoes through Chinese history and captures this grim reality is: “飞鸟尽,良弓藏;狡兔死,走狗烹” (When the birds are gone, the good bow is put away; when the clever rabbit is dead, the hunting dog is slaughtered). This proverb, uttered by the great general of the Spring and Autumn period, Fan Li, sums up the ruthless practice of eliminating those who helped you rise to power once they were no longer of use.

The Tragic Tale of Emperor Liu Bang: A Foundation Built on Blood

Liu Bang, the founder of the Han dynasty, is often hailed as a clever strategist. Despite acknowledging his shortcomings in battle and governance, he was a master at choosing capable men. But in his pursuit of securing the throne, Liu Bang set a bloody precedent.

After he established the Han dynasty, Liu Bang generously rewarded his supporters—people like the great generals Han Xin and Peng Yue, who were elevated to powerful positions, and various others were bestowed titles of kings. However, these were not acts of charity. As Liu Bang consolidated power, these loyal figures quickly became liabilities. Liu Bang’s paranoia led to the execution of several former allies, including Han Xin, who was originally made King of Chu but later executed on charges of treason, and Peng Yue, who was also killed after falling out of favor.

While Liu Bang’s reign was violent, it wasn’t entirely reckless—unlike some of his successors, who would take mass purges to even greater extremes.

The Grim History of Southern and Northern Dynasties

Fast forward to the chaotic Southern and Northern Dynasties period, where the Chinese empire was fragmented and warlords battled for control. This era, often described as one of the darkest in Chinese history, was marked by widespread bloodshed, not just on the battlefield but within the palace walls. The emperors of this time were notorious for their cruelty toward their own officials and ministers.

Take, for example, the Southern Dynasty’s Liu Yilong, who after ascending to the throne, ruthlessly killed his key supporters like Xu Xianzhi and Fu Liang—who had helped him claim power. Similarly, Emperor Xiao Wu of the Southern Qi dynasty is said to have purged his own family and ministers, executing anyone who posed a potential threat to his throne. The cruelty became so rampant that it would eventually lead to the downfall of the entire dynasty.

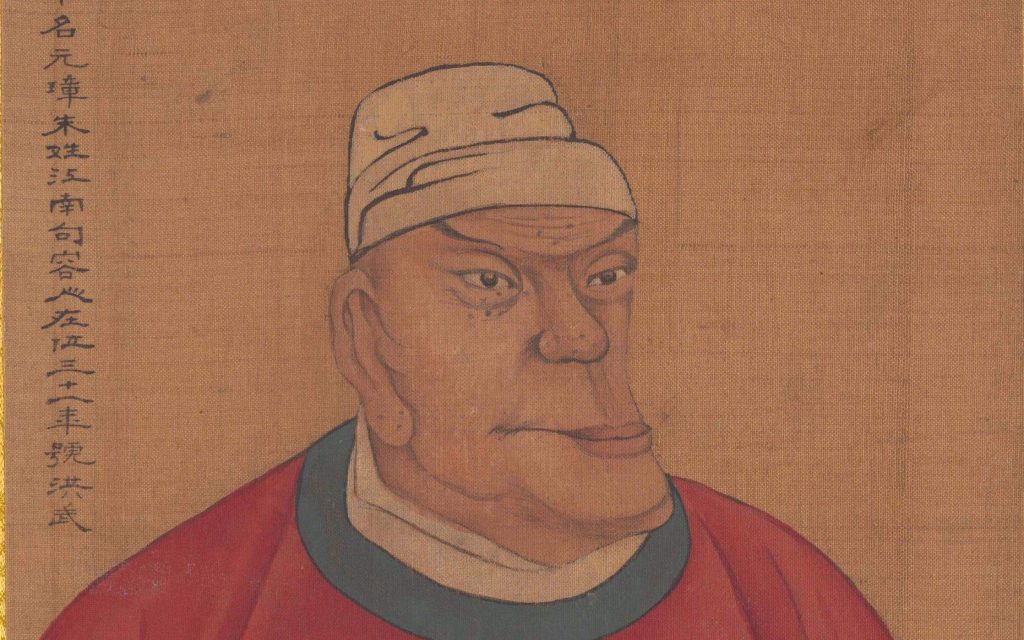

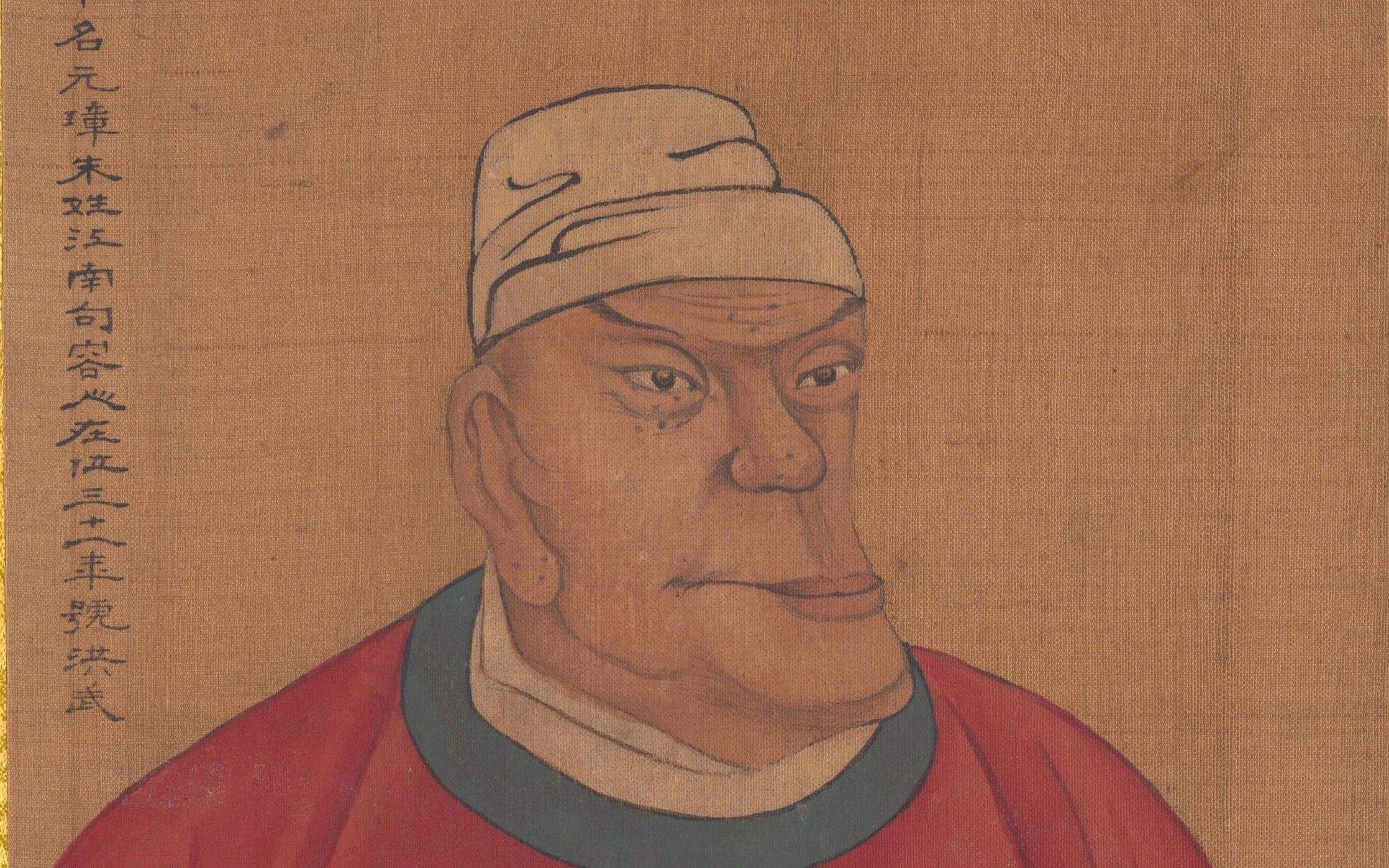

The Ultimate Paranoia: Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang

The most infamous of all, however, is Zhu Yuanzhang, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty. Unlike many of his predecessors, Zhu Yuanzhang’s paranoia seemed to know no bounds. A common phrase attributed to him, “I am only killing those who deserve it,” was meant to justify the mass executions he orchestrated—executions that took the lives of not only his enemies but his closest allies, who had helped him rise from an impoverished peasant to the ruler of all China.

Zhu’s paranoia culminated in the brutal purges of his most trusted generals, like Xu Da and Li Shanchang. The most chilling aspect of his rule was his willingness to eradicate the very people who helped him achieve victory. One such case was that of the general, Hu Weiyong, who was accused of treason and executed, along with thousands of his supporters.

Zhu’s violent methods weren’t without reason. He believed that by eliminating any potential rival, he could secure his dynasty for future generations. Yet, this deep distrust and obsession with eliminating “traitors” only left the Ming dynasty with a history tainted by internal bloodshed.

Cultural Impact: A Legacy of Fear and Paranoia

The ruthless acts of these emperors didn’t just shape the political landscape—they also influenced Chinese culture. The concept of loyalty, once considered sacred, became deeply entangled with suspicion and fear. The idea of the “emperor’s paranoia” found its way into Chinese literature, where it became a recurring theme in historical dramas and novels. In these stories, we see the reflection of a culture where even the closest allies could not escape the bloodlust of the ruler they helped to ascend.

Moreover, the legacy of these tyrannical rulers influenced not just their contemporaries, but future generations of Chinese leaders. The idea that “absolute power corrupts absolutely” seemed to be ingrained in the imperial psyche, leading to cycles of betrayal, violence, and eventual decline.

In the modern world, the influence of this historical trend can still be seen in both political and corporate structures. The constant battle for power and the paranoia that often accompanies it continues to affect global politics and organizational behavior. While we no longer see emperors ordering the execution of their most loyal followers, the underlying fear of betrayal is a timeless theme that transcends history.

No comments yet.