When was the last time you wrote a date and thought, “Wow, that’s a nice, modern, globally standardized Gregorian calendar”? Probably never. But believe it or not, how we mark years is a serious business—one that ancient civilizations took very seriously, especially the Chinese. For over 3,000 years, the Chinese never missed a beat when recording history, using some of the most inventive, symbolic, and occasionally confusing calendar systems the world has ever seen.

Let’s time travel through China’s fascinating chronicle of year-counting methods, a saga full of emperors, astrology, political drama, and… occasional calendar confusion.

👑 The Original Time Bosses: Reigns & Kings

The earliest method was the “Regnal Year System”, where time began anew with each monarch’s reign. If the Duke of So-and-So took the throne, Year One began right then and there. This method was widely used in the Zhou Dynasty, and later in various feudal states. The famous ancient text Zuo Zhuan uses this system religiously. When you read “the tenth year,” it’s not about 10 AD—it’s Year 10 of the ruler’s reign.

Interestingly, the first precisely dated year in Chinese history is 841 BC, the “First Year of the Republican Era” (Gonghe Yuan Nian), which, ironically, wasn’t even during a monarch’s rule. The previous king was kicked off the throne for being a tyrant (classic), and a regency government stepped in. It’s a bit like saying, “Welcome to Year One of No One’s In Charge.”

🏯 Emperor Branding 101: The Era Name System

By the time of the Han Dynasty, things got more stylish. Enter the “Era Name System” (Nian Hao), where each emperor got to name an era, often based on a significant event or desired symbolism. The year counting started anew with every new name. The famous Han Wudi (Emperor Wu of Han) had eleven different era names during his 55-year reign. That’s more rebranding than some tech startups.

The queen of all name-changers? Empress Wu Zetian, who had 18 different era names in just 21 years. If you lived under her rule, you’d be changing your calendar headers more often than you change passwords.

In later dynasties like the Ming and Qing, the trend settled down—one emperor, one era name. This led to emperors being remembered by their reign title, like Emperor Kangxi or Emperor Yongle. But the politics of naming didn’t stop there. During the Kangxi reign, over 70 scholars were executed for refusing to use Qing era names in historical texts. Yikes.

🎎 Cultural Ripples: China’s Calendar Goes International

The Era Name System wasn’t just a Chinese phenomenon. It spread across East Asia, adopted by Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Japan, in particular, has kept the tradition alive for over a thousand years. As of 2019, Japan had gone through 247 era names, the latest being “Reiwa”—which, in a historical twist, was taken not from a Chinese classic, but from Japan’s own poetry anthology Manyōshū. That’s like naming your reign after Taylor Swift lyrics instead of Shakespeare.

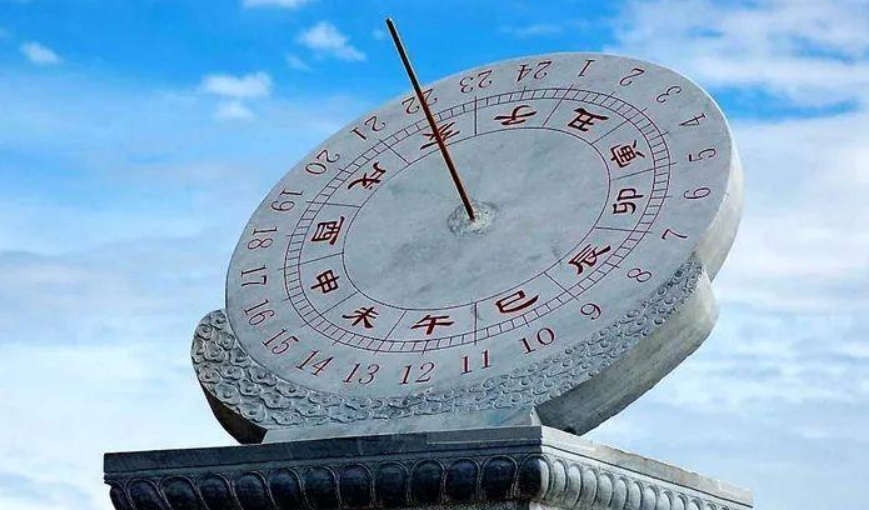

🔮 The Zodiac Spin Cycle: Heavenly Stems & Earthly Branches

Still in use today is the elegant and mystical Sexagenary Cycle—a 60-year rotation using combinations of Ten Heavenly Stems (like Jia, Yi, Bing…) and Twelve Earthly Branches (like Zi, Chou, Yin…). This pairing system traces back to the legendary Yellow Emperor, used originally for divination and ritual, later repurposed for tracking time.

The first combo in this cycle is “Jiazi,” and every 60 years the sequence restarts. Major events are still often named this way—for example:

- 甲午战争 Jiawu War (1894) – First Sino-Japanese War

- 戊戌变法 Wuxu Reform (1898) – Failed political reform in the Qing Dynasty

The combo system can be precise to a single year but gets a bit tricky when looking back across millennia. Which “Jiawu” are we talking about again?

🗓️ Mix-and-Match Dating: Getting Precise with Time

To fix ambiguity, Chinese historians got creative and combined dating methods. A document might say something like: “Tianqi Renxu Autumn,” which tells us both the reign (Tianqi, of the Ming Dynasty) and the year in the 60-year cycle (Renxu). It’s like saying, “This happened during Obama’s second term, in the Year of the Dragon.” Hyper-specific, culturally rich.

🎉 Event-Based Timelines: When Big Moments Start the Clock

Sometimes, people picked an important historical event or figure’s birth as Year One. The Huangdi Era counted from the mythical Yellow Emperor’s birth (2698 BC). The Republic of China (ROC) calendar started from 1912, when the Qing Dynasty was overthrown. Taiwan still uses this method today alongside the Gregorian calendar.

This dual-system once caused a humorous hiccup. The author of the original Chinese text recalls meeting a Taiwanese exchange student wearing a badge that said “Born in Year 76.” He thought she was born in 1976. She was actually born in ROC Year 76, aka 1987. Oops.

🎯 Culture, Continuity & A Dash of Common Sense

So, should we ditch the Gregorian calendar and go back to “Jiashen Year of the Ruler Zhaobing’s Era of Eternal Harmony”? Probably not. While it’s tempting to revive ancient systems for the sake of cultural pride, practicality tends to win out.

What is worth celebrating, however, is how deeply embedded timekeeping is in Chinese civilization’s DNA. With thousands of uninterrupted years of recorded history, China’s legacy of marking time is a testament to its continuity and resilience.

And hey, whether you’re living in 2025 or Kangxi Year 364 (okay, not really), time still ticks the same—it’s how we choose to tell the story that makes it magical.

No comments yet.